Indigenous artist Rheanna Lotter has collaborated with Specsavers to empower communities to prioritise eye care, and prove that art can bridge cultural gaps

Rheanna Lotter is no stranger to the transformative power of art. A proud Yuin woman who grew up in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, she once aspired to be a professional athlete. But on a return trip to her childhood home, she found solace in the act of painting. It gave her the tools to tell her stories – and opened up a path she’d never considered.

“Mum had some paints out, so I painted a platypus,” Lotter smiles. “[At the time] I hadn’t seen my grandparents on my Indigenous side for a while and the painting just sparked this creative feeling in me, this connection to who I am. I started sharing art on my social media and that led to the Blak Markets [at Carriageworks], where I first got noticed. It just grew organically from there.”

Lotter started painting under the name of Ngandabaa, pronounced yun-da-baa, a business she founded and named after Keith Thorne, her grandfather, a lifelong source of inspiration.

“It means red belly black snake, my grandfather’s totem,” she says. “[When he] passed, he was really proud of what I was doing. He had such an impact on people who knew him.”

Through Ngandabaa, Lotter has focused on making art that celebrates her connection to her culture while fulfilling a social mission. In 2017, she was approached to design uniforms for the Australian Paralympics team. Her artwork, which featured circles and lines representing the journey that binds Paralympians together, was on display at the 2021 Tokyo Paralympic Games.

Two years later, she was approached by Specsavers to design a limited-edition pair of glasses with the aim of raising money to help close the gap in vision loss between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other Australians. Cathy Rennie Matos, head of public relations at Specsavers, says the optical group was drawn by Lotter’s commitment to social justice.

-

Rheanna Lotter’s Limited Edition Specsavers frames are available in sunglasses and optical.

“Rheanna wanted to work together in a way that raised awareness for both Indigenous art and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander eye health,” Rennie Matos says. “We are really blessed that she has leant her art to this project and to hear about her heritage.”

The initiative, which grew out of a long-term partnership between Specsavers and the Fred Hollows Foundation, began a decade ago, fuelled by a shared commitment to making eye care accessible to all segments of society.

It started with a commitment to providing eye health services to Indigenous communities in places such as remote Western Australia through ventures such as the Lions Outback Vision Van, a mobile eye health clinic operated by one of the foundation’s program partners, the Lions Eye Institute. According to 2019 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 38% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people suffer from vision impairment. They are three times more likely to go blind than the wider population.

“We identified some artists who had actually been the recipients of cataract surgery that had been organised by the foundation,” Rennie Matos says. “As soon as they had the cataract surgery, they were able to see again, and importantly get back to their painting.”

Specsavers partnered with Indigenous artists who had experienced cataract surgery, such as the late Langaliki, and Peter Datjing, a renowned painter from north-east Arnhem Land. These artists gave permission for their work to be transferred onto the limited-edition frames, highlighting the way the foundation’s work enables them to carry out their artistic vocation.

But these limited-edition collaborations, which donate $25 from each pair of glasses to the Fred Hollows Foundation, and which have raised more than $400,000 to date, also use art to raise awareness of Indigenous visual culture. The initiative closes the gap when it comes to Indigenous eye care and empowers communities to prevent problems that could affect their vision down the track.

Last year’s limited-edition frames were adorned with Lotter’s Saltwater Dreamin, a striking blue artwork featuring black-and-white turtles, which drew attention to the importance of protecting waterways. Lotter says Specsavers shared her vision for helping vulnerable communities, and understood how art can hold a mirror up to defining issues.

“I love to paint about the environment and people forget that there are living animals that rely on us,” she says. “Our values were so aligned [towards] making our society better, especially for people from vulnerable communities. We were like two peas in a pod.”

Lotter’s visual language celebrates connection. Forms are often joined by lines, evoking threads that join us. Shapes recur, speaking to our similarities.

-

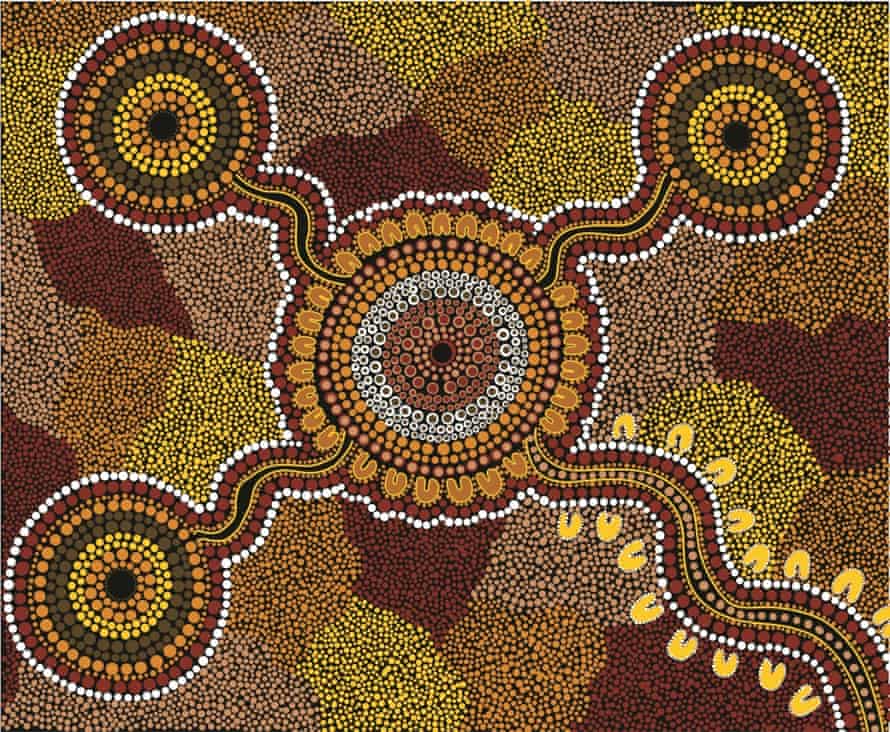

Rheanna Lotter’s artwork, Unity.

Lotter says some of her paintings take careful planning. Others are a matter of following her creative instincts. In the case of Unity, she wanted to convey how urgent it was for all Australians to come together, despite historical and cultural barriers.

“It’s about coming together, moving together, acknowledging our past and planning for a brighter future for everyone,” she says. “It’s about being guided by our elders and our ancestors and not brushing over things that are difficult.”

In Unity, she says, the circles are highly symbolic.

“Circles for me are really significant,” she says. “[They] are a meeting place. It is about how we are all equal and valued. The circle doesn’t break. The ‘u’ shape is about us sitting down and having tough conversations. Everything in Unity has a story to tell.”

Lotter hopes Unity will spark conversations that can ripple through society.

“[It’s] really important to talk about relationships, about how art brings us together,” she says. “It’s a form, like music, where you can listen to a song and say, ‘I relate to that, I feel that’. With my paintings, you can understand the symbolism.”

Lotter believes that in Indigenous culture, art is an “unwritten language”. In the case of her collaboration with Specsavers, she hopes that this language will raise awareness of the importance of connection – while inspiring communities to access support.

“I hope that by seeing the artwork on the frames, learning more about me, it makes people feel comfortable,” she says. “I don’t want people to think that Aboriginal art is just on a canvas or on a cave – it’s part of our history, part of us.”

Links: https://www.theguardian.com/specsavers-an-eye-for-art/2021/nov/11/sight-unseen-how-artist-rheanna-lotter-is-drawing-attention-to-indigenous-eye-health